The Illusion of Opportunity Cost

The "Hills Principle": Good things can happen when we build anything

I was recently working with a founder who was trying to build a new kind of payments/financing platform that could theoretically work in nearly any sector.

He said, “We finally found a potential great partner who is an industry leader in real estate. They could really get us started because they can bring in a lot of appealing deals, but they aren’t interested in the platform as a general tool. This could be the opportunity we’ve been waiting for, but I’m worried about getting locked into one industry. If we go too hard and build a product for just real estate, will it pigeonhole us and keep us from expanding to other places in the future?”

I said, “You only have so much effort to go around, and you have a fantastic partner available. You have to start somewhere, and go really deep in one industry before you can generalize. Why wouldn’t you take the victory and run?”

“Because,” he responded, with the exhaustion of a year’s worth of setbacks in his voice, “What if it turns out down the line that real estate isn’t the best industry to expand from? What if we put all our effort into building a real estate product, only to find that we have to build something else?”

Daunting Choices

This is actually a question I get all the time. Especially when you are just starting out, the opportunity cost of making the wrong move looks gargantuan. Building even one product, any product, already feels daunting. So nothing is more demoralizing than the fear that you might put in all that back-breaking labor, money, and time only to find out that you needed to build something else all along.

But don’t be disheartened.

It’s actually completely inevitable that you will build the wrong thing. In my entire career across hundreds of companies, I have had exactly one team get the right idea on their first try.

But — that doesn’t mean that the opportunity cost of building the wrong thing is actually very high at all. The opportunity cost is an illusion. It’s much easier and faster to build the wrong thing and change directions than it is to stay put until you’re ‘sure’ about which direction to take. I have seen companies spend 6 months or more trying to pick the correct direction, when shifting between ideas would only have taken 2 months.

The reason why is that the act of building and testing the wrong thing makes us astronomically more capable of building the right thing.

How Opportunity Cost Actually Works

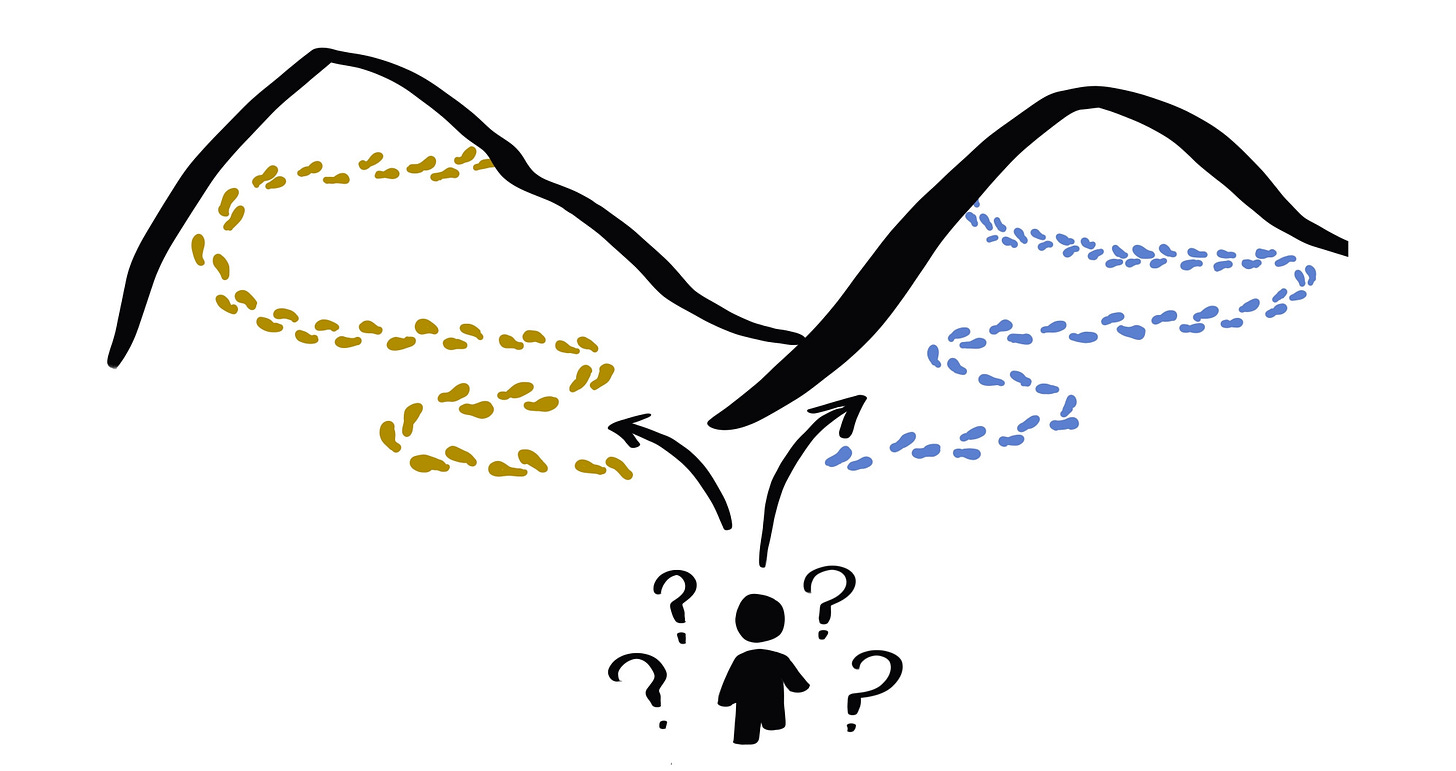

Imagine you are a small creature, trying to figure out which of two enormous hills to climb. Like this:

You can take all your resources and go up one! But from where you stand, it seems like if you burn all your energy climbing The Wrong Hill, you’ll be stuck there, or you’ll fall into that pit in the middle and never be able to climb back up to the other one!

But this is what actually happens:

After all that climbing, you’re huge!

In the course of climbing the first hill, you will grow so much in terms of learning and capability that, instead of 1000 steps to get to the top of the second hill, it might take you just 15 steps.

Furthermore, from the top of the first hill, you can see a lot further than you could at the beginning. The perspective you gain from building and testing any semi-viable solution reveals more of the entire solution landscape to you.

At this point, you realize that the initial choice of which direction to take that had you so stressed out, was actually a false dichotomy: the real solution lies beyond both of them in a place you couldn’t previously imagine.

Those two initial hills are just the beginning, not the end, of your journey.

As with my funding platform friend whose perfect first partner was staring him in the face, the only thing left to do is start climbing.

The Checklist

But how do we know we’re striking the right balance between getting moving and not over-investing? If the first hill is not the right one, how will we know when we are in the right place?

Try reflecting on these questions:

Is the real purpose here to explore and understand, or to invest and scale? (Am I trying to get to the top of this hill in order to be there, or just to see from there?)

What am I trying to learn through this experiment/project/product version/partnership?

What is the right level of resources and commitment for me to invest in order to learn that information, while maintaining my agility once I get to the top?

Am I confident that my users love my solution? If not, what parts of it hold a spark of love that I can follow to a new hill?

As long as you keep just keep climbing hills, you cannot fail to someday find your true north. (As Anna says in Frozen II, “Do the next right thing.”)

There is no map— along that journey, you will never truly feel like you know where you’re going.

Instead, one day you will simply look up and realize that you are already there.